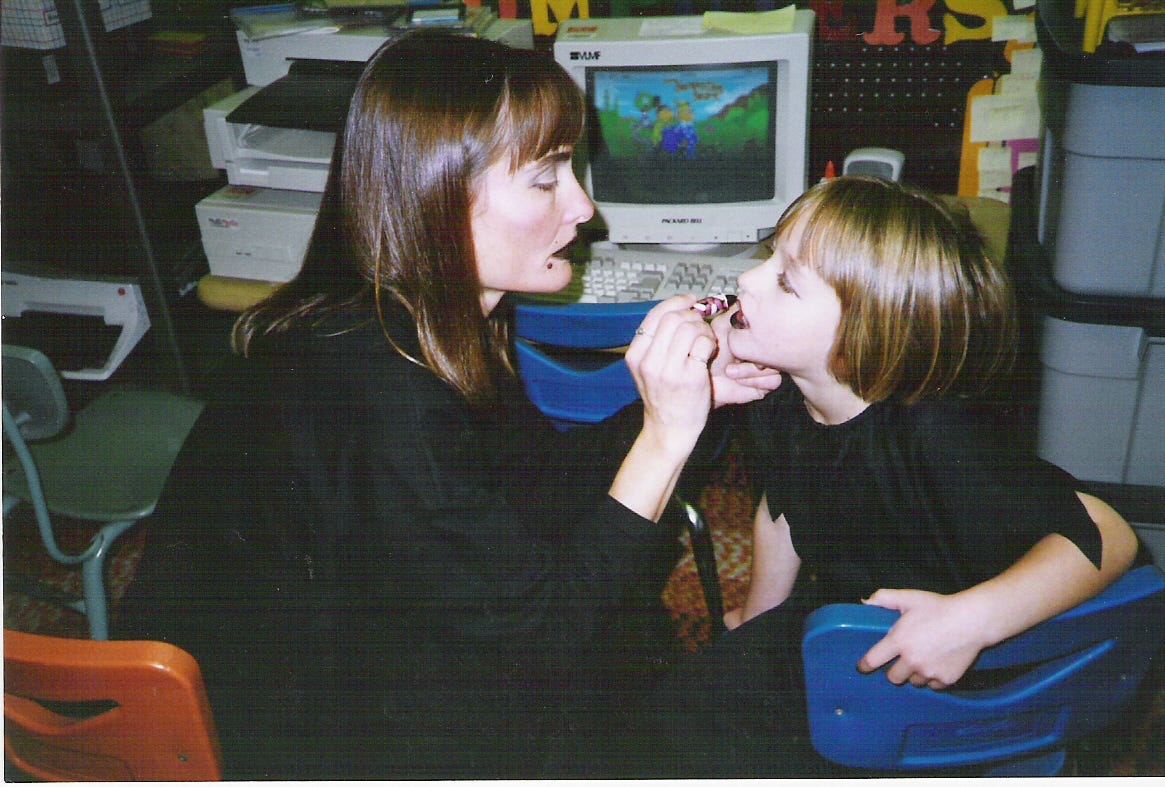

A name is like a snapshot. The part of someone that becomes an entry point. The farthest outward layer of them—a place, a location—where you first connect.

If you are a house, then your name is the street. It tells me something about getting to you.

I connect with you first at the farthest, most accessible edges of you, your name being one of them. I go to your house by knowing which street it is on.

Hello, M. Hello, O. Hello, V. My name is S.

We acknowledge each other by naming each other, then we continue.

The continuing happens in any variety of ways.

In some sense, naming each other is the first thing any two people do together. We name each other, and only then do we come to know each other.

Or, we begin to know each other right as each other’s names start frequenting each other’s peripheral awareness. A simultaneous blossoming of texture: the texture of names.

Or, from afar, I decide I’d like to know you, and so I begin the small work of gathering and storing your name, knowing it will allow me to greet you when the greeting work is ready to occur.

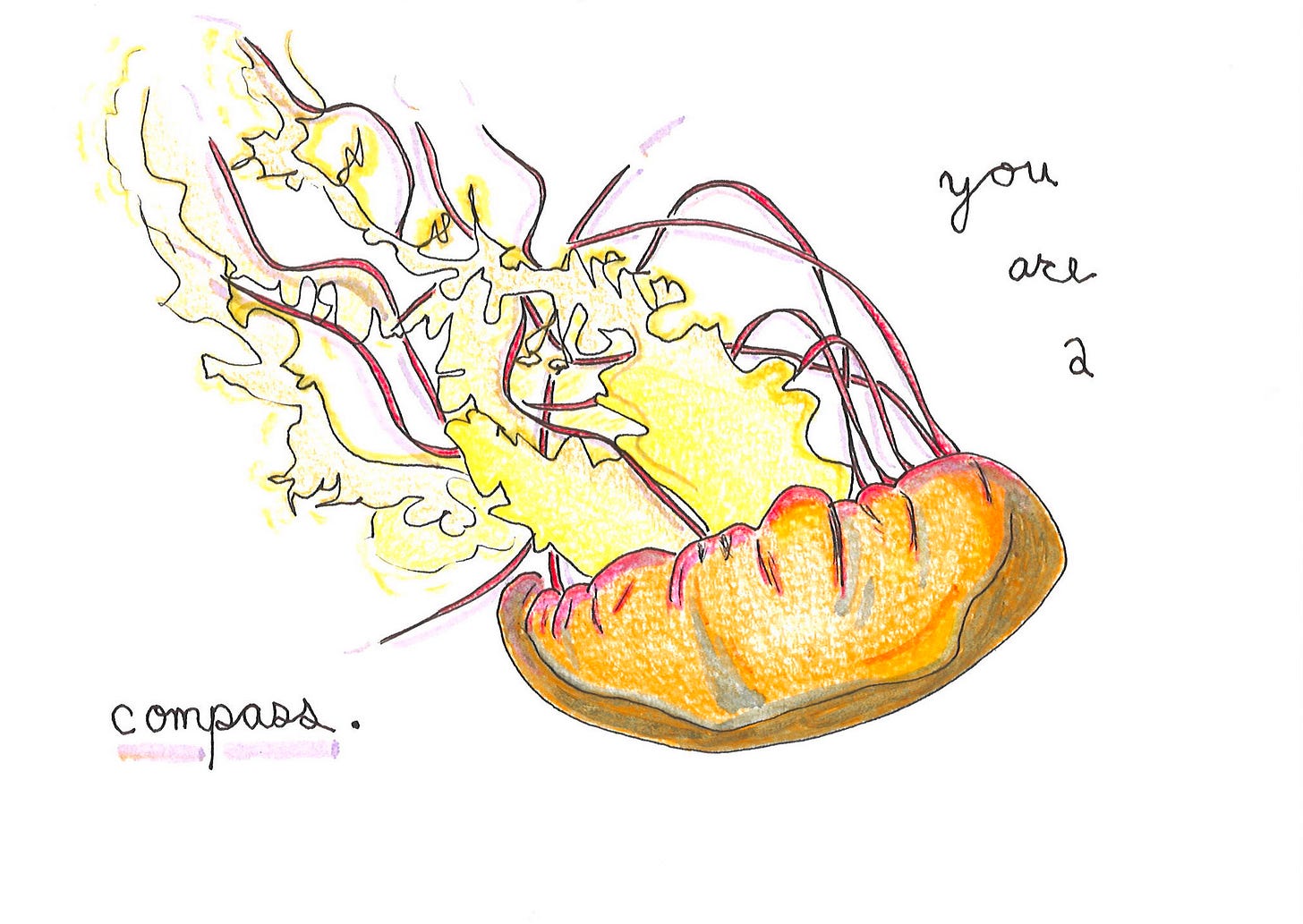

In these and other circumstances, it happens through learning: the acquisition of someone’s name, like a manual, like a passcode, like a description. A name can be all three: how I come to read you. Something that gives me access to you. The place where my little knowledges and assumptions about you gather and form and rest—the way knowing is built of rest.

Sometimes it happens through creation: the assigning of someone’s name. Like a gift. Like a decision. Like a commitment.

This is B. This is N. This is P. Now the relationship—between you and the world—between me and you—begins.

And when the name goes away?

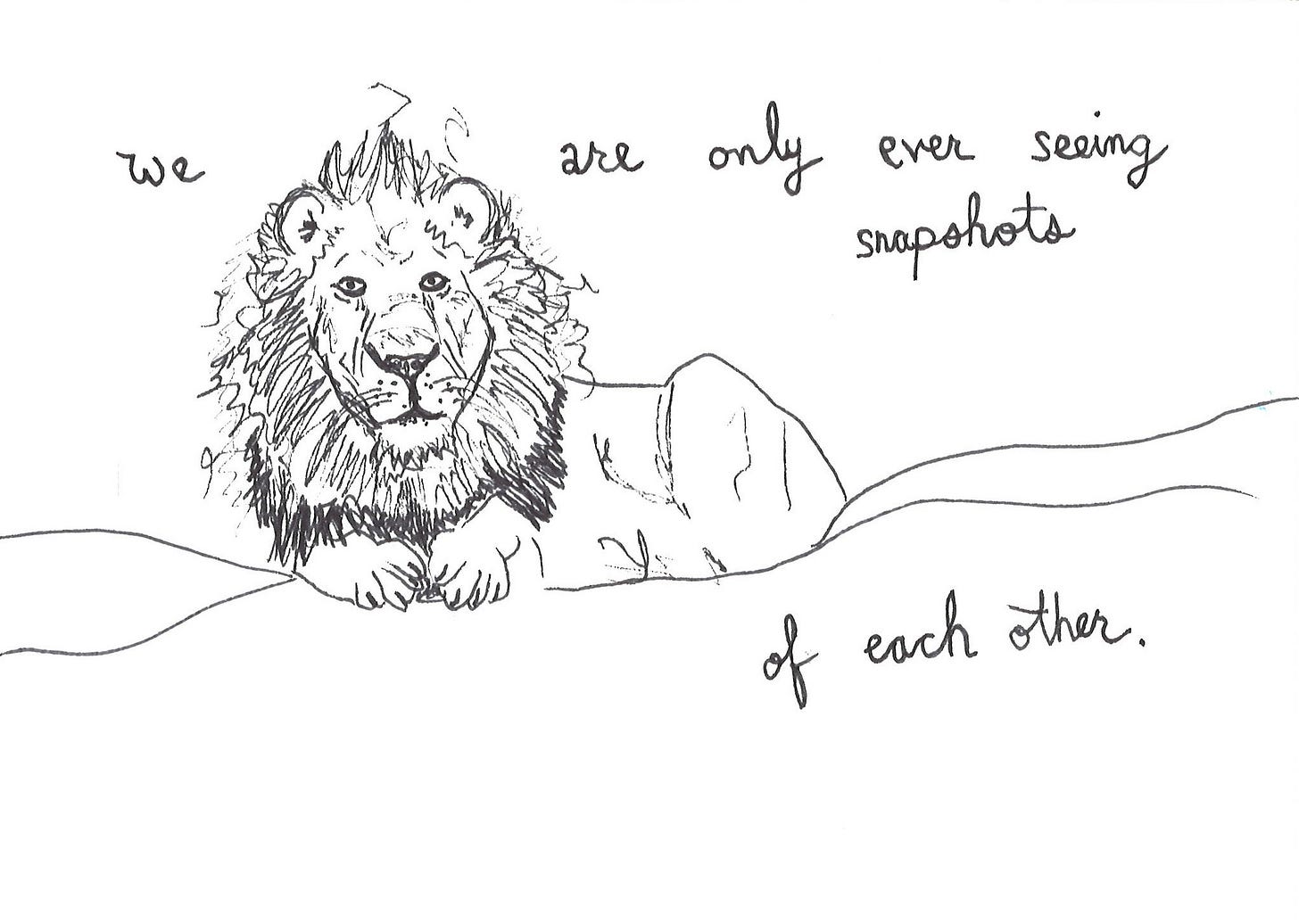

Consider the sycamore: wide-canopied, deciduous. Skin—we’ve named it bark—that is at once rough, sloughable, but also incredibly smooth. A simultaneous blossoming of texture. You walk through your neighborhood early one evening, anticipating the full moon, and can’t help but touch the trunk of every single one you see.

All this without ever once giving or receiving or acknowledging its name. “Sycamore” is what we call it. It doesn’t matter. It sheds its leaves regardless. It does what it does without knowing about what it does. It cycles and grows, regardless of designation or description.

And when the name changes?

I once learned a name. Or I had it. Or it was given to me, but before the idea of me.

Or: it was the idea of me, but the thing of me proved different than the original idea. Bigger and smaller. Just weirder. Plus it wouldn’t stop growing, me. As if I might outgrow each pot I was placed in. As if I might outgrow the ground itself.

The name stuck until it couldn’t anymore. Or until I pulled it up, roots and all, in one swift moment of pulling. Or until the longest summer turned fall, and everything once pretty suddenly dropped for good reason. Or until I noticed it was never pretty, and never my own, and made the decision to be more accurate about my living.

“Before her birth was she an idea? Before her birth was she dead? And after her birth she would die? What a thin slice of watermelon.” ~Clarice Lispector, The Hour of the Star

People congratulate women on their new names because they assume it means holy matrimony.

Call me Skeezix. Call me Anastasia. Call me princess, lady of high rank, wife of Abraham. Call me Sar-bear, Sahara, Sar-dog, or Sir. Que Sera Sera. There’s nothing tender about the inquiry: we just want to know if we will be rich, if we will be pretty, if our sweethearts plan to give us their last names. If I will become a new person and, if so, how long it will take. How long it took for “Cocco” to become “Cook.” How many generations it takes for a made-up name to become a real one. What my name looks like when you view it from the farthest edges of me, the edges I can only access from within my place here in the middle. Or rather: what I seem like when you stand at those edges, my edges, say hello, and lean toward me. What I seem like based on what you call me.

Everything1 goes through me, including words, which are only names in different clothing. I understand all of it—the words, the dress, the styling—through my own experiences of it. Through “strong objectivity.” I cannot know the Sycamore outside my experience of the Sycamore. I do not call your name without conjuring all my personalized associations with it. I say, “thank you,” when people congratulate me, because it’s true that something took place that was holy, and was steeped in unification, and was born of the Latin word, matrimonium, based on mater or matr, “mother.” I marry my own intentions. I take the Sycamore as a wife. I wed the edges of myself to the crisp fall air, which is getting colder, so we fight sometimes. My skin—in this desert-like winter I call it bark—protects me, and I don’t acknowledge that armor enough.

I sit at the edges of me and lean, lean, lean toward the middle. I lean and I gather and I form and I rest. I re-name my self. I call her, “valuable.” I conjure the person she is trying to refer to. In the middle of all this hubbub I find real, genuine, made-up people, slice after slice after slice of watermelon.

Suggested homework

Give yourself an endearing nickname

Use a fake name the next time you’re ordering coffee

Celebrate Samhain

Call your mother

“I want to see everything now. And while none of it will be me when it goes in, after a while it’ll all gather together inside and it’ll be me. Look at the world out there, my God, my God, look at it out there, outside me, out there beyond my face and the only way to really touch it is to put it where it’s finally me.” ~Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury.

You wrote this so long ago, but it just made my day. How refreshing. Thank you 😊