For the Birds: Traveling while neurodivergent

Personhood, un/masking, & being away from home. Plus: Travel tips for soothing yr divergent brain.

Thanks for being here! Paid readers of For the Birds directly fund the growth & longevity of this creative project, while gaining access to The Resiliency Circle and monthly creative prompts.

When you can, thank you for reading closely, sharing widely, and financially supporting this newsletter.

Learning to notice the self

One of the strangest things about receiving a life-changing diagnosis is the way it incites a whole new set of firsts.

First time hanging out with a best friend as an Autistic person. (Result: It was the same as before! But in a totally new / exciting / scary way.)

First potluck as an Autistic person. (Awful—though they always have been. Now I’ve sworn them off for good.)

First live show as an Autistic person. (My personal brand, if I really must have one, is “averted eyes.”)

First in-person class as an Autistic person. (Oh my god: I don’t think I’m shy! I think I just prefer not to talk to people in most situations.)

First trip as an Autistic person…

Mid-July, I spent 9 days in the south celebrating a pivotal family birthday and briefly visiting some extended relatives. I made choices about when to mask and for how long; about which feelings to communicate and which to reserve for nightly journaling; and I wore a rainbow infinity necklace most days with the vague hope that others—people I know, people I don’t know, literally anyone—might see it and proactively understand something about me, might approach with a little more softness or broader expectations.

But mostly, I wear it as a private reminder to be confident in my own reality.

What I’m telling you, of course, isn’t true—I have always been an Autistic person. My Autism is not new, only my knowledge of it. But not understanding my inner-workings for 36 years meant not recognizing the full scope & veracity of my needs for 36 years either, which meant relating to myself ungenerously and reading the bulk of my otherwise neutral impulses through the lenses of bias and fear.

Example: I have a very hard time in traditional social situations; I sometimes have lots and lots of language, and sometimes very little; and I struggle to regulate my emotions. My historical assessment of these qualities is that I must be inhuman, secretly not very smart, and fundamentally immature and/or “crazy.”

Learning to notice the real self

Enter: The work of unmasking, and the gift it offers of neutrality and, eventually, self-acceptance.

In my limited experience so far, one of the strangest things about this unique healing process is that it isn’t a direct or linear one. Understanding that I am a masked person is only one part of it. (Do I pretend to be okay in those very hard social situations? Do I struggle to own my expressive limitations? Do I constantly assess myself through other people’s impressions of me? Historically: Yes, yes, and yes.)

But unmasking involves acting differently—being actively unmasked—which means recognizing both the inauthentic performance and the authentic state beneath it.

How do you recognize someone you’ve never seen before?

What I’m trying to say is that taking a mask off doesn’t really explain this work, just like calling Autism a “spectrum” still flattens out the complex constellation1 of experiences, needs, and limitations that intersect and make every single Autistic person different.

Learning to recognize the previously unrecognizable self is slow, strange, hard, and time-consuming. I don’t always see a new part of myself and just know that it’s right and true; I have to enter the changing room called, “Personhood?,” and try it on—see how it feels, notice where the seams land and what still needs hemming despite a mostly-good fit. I have to wait for my intuition—the part of me that does know things on occasion—to show up in the unhurried, irreverent way that it does. For every lightning bolt moment of new self-insight, there are at least twice as many labored, unglamorous, maybe-this-is-right moments that only look true, and only make internal sense, after the fact.

Nothing I’m saying here is bad or wrong, by the way.

Neurodivergence isn’t a thing to fix, just like Autism, no matter what the DSM has codified, isn’t a disorder, but a diversion from what’s been deemed to be, over time and by those with the most social power, “normal.”

Which means my own healing journey isn’t about speeding up or bypassing those changing room moments. Instead, it’s about learning how to show up to and for myself in the meantime.

Meantime is the only time we really have, don’t you think?

Here’s another idea I am trying on: I picture “unmasking” as the process of restoring a large Renaissance oil painting; it’s a putting (back) on as much as it is a taking off. Think of the complex intersection of strategy, fine motor detail, and best guesses that go into returning something to its original state, especially when you can’t ask the artist / past self direct questions.

The changing room of personhood

Sometimes, I catch myself masking in real time, but don’t feel capable of doing anything about it.

I’m practicing reading this as its own kind of accomplishment.

The accomplishment of being with myself, masked or otherwise, in real-time.

I’m still there. She’s still me.

So when I say I “made choices” on my recent trip, what I mean is that I sometimes expressed a need fairly soon after becoming aware of it; and that I sometimes did things proactively to help myself orient to the new setting I was in; and that I sometimes changed my mind about social obligations at the very last minute, not from a place of confidence but from a place of or else I am going to burst-ness; and that I sometimes could not make any choices at all, like the day I holed up in my room and, when asked if there was anything he could do to help, told my partner that all I wanted was for someone to say something to me that would make me yell at them.

It was one of the truest, most unmasked things I have ever said.

In the end, I did not yell. Maybe I should have? No, but maybe I’d still like to, not about or to anything or anyone in particular, but simply to hear my unfiltered capacity run face first into the wall of the world.

I am practicing being okay with my humanity as-is, and daring to think that an impulse in me could be something other than bad or wrong, those twin assessments that haunt too many of us.

As for the logistics of traveling as a highly sensitive, neurodivergent human being, I’m sharing below some of my biggest takeaways for how to meet my needs while away from home base. I share these biased insights with my researched + lived experience of Autism front of mind, though let me be clear: All brains can benefit and receive comfort from divergent practices.

Traveling while neurodivergent

~an incredibly biased / possibly underwhelming / hopefully helpful list~

1) Put all your things away when you arrive

The very first thing I did when I landed—before eating, before resting—was put my things away. I hung my clothes. I laid things out over chairs when I ran out of hangers. I set my book light on the nightstand. I didn’t just plop my bathroom bag next to the sink; I unzipped it and set things in the shower, on the shelf, and on either side of the faucet in an organized manner. I made temporary places for things, which immediately created familiarity and a sense of order that I could check back in with at any moment of my trip. (Yes: toothbrush goes here. Yes: earrings go there. Belongingness!)

2) Look up menus in advance

This is a really common practice for many Autistic folks, as is clarifying in advance what the layout of a restaurant is, where the bathroom is located, etc. There’s something about the combination of getting our bearings more slowly, and taking in more data at all times, that makes this kind of proactive information really, really helpful.

3) Bring something intimate / comforting from home

Here’s my version: Moving forward, I am never, ever, ever going to travel without a silk pillowcase, which I realize sounds like the bougiest thing in the world, but it’s what I’ve slept on for years (it’s good for yr skin and hair, ya’ll!). This one felt like such a lightbulb moment for me, because a) it takes up almost no room in my suitcase, and b) it means maintaining a nighttime comfort / sensory experience no matter what strange new pillow I find my head on.

4) Puncture your trip *proactively* with solo time

My partner knew we were going to need a solo day. He just knew. And he told me beforehand, to which I said, naw, I don’t think that’s a good idea.

It was a mix of stubbornness / denial / and the divergent pace of my knowing. I had to stumble my way into recognizing this need in (almost) real time, and was (eventually) able to communicate it to our host, naming out loud that I need regular time and space to re-set myself. It isn’t merely a response to stress; it is a vitamin my body needs extra high doses of. And it is a thing I will be proactively planning for all future trips.

5) Stock up on familiar beverages / treats

Our extremely thoughtful host had already stocked the fridge with La Croix and Liquid Death, which we supplemented with some Sol-tis (both the blue full-sized bottles and the tiny shots). Having familiar beverages & special favorites on hand made staying hydrated feel like a ritual—part stim, part spellcasting.

6) Be strategic about therapy

Being gone for 9 days meant missing a full week of therapy. I made sure, weeks in advance, to have a therapy session scheduled for as soon as possible after our return, regardless of what day it fell on. (And also, as it turns out: I didn’t need it! I mean, I see my therapist twice a week, and we always run out of time: I need therapy.) What I’m saying is that I did not show up to that next session with any kind of emotional urgency, but that having it waiting for me provided an incredible peace of mind.

7) Manage your sensory input

I’m knee deep in thoughts about sensory input and the strange practice of learning to notice things about my body and nervous system that I have avoided knowing for years and years. There’s a lot more to say about this—the way we can learn to tolerate things that are so destructive to our wellbeing, and the way we can feel like frauds when we are suddenly confronted with our inability to tolerate them any longer. But for now, let me tell you about two well-documented Autistic supports that have totally reshaped the emotional quality of my daily living:

Headphones. I’m late to the game here, but wow are headphones so so wonderful and indispensable. Sometimes I don’t even have anything playing—the signaled boundary of wearing them + physical pressure on my ears can be enough.

Earplugs. I promise I’m not an affiliate or receiving sponsorship of any kind, but I have to tell you how much I freaking love my Loops.

8) Make it easy to access yr creativity

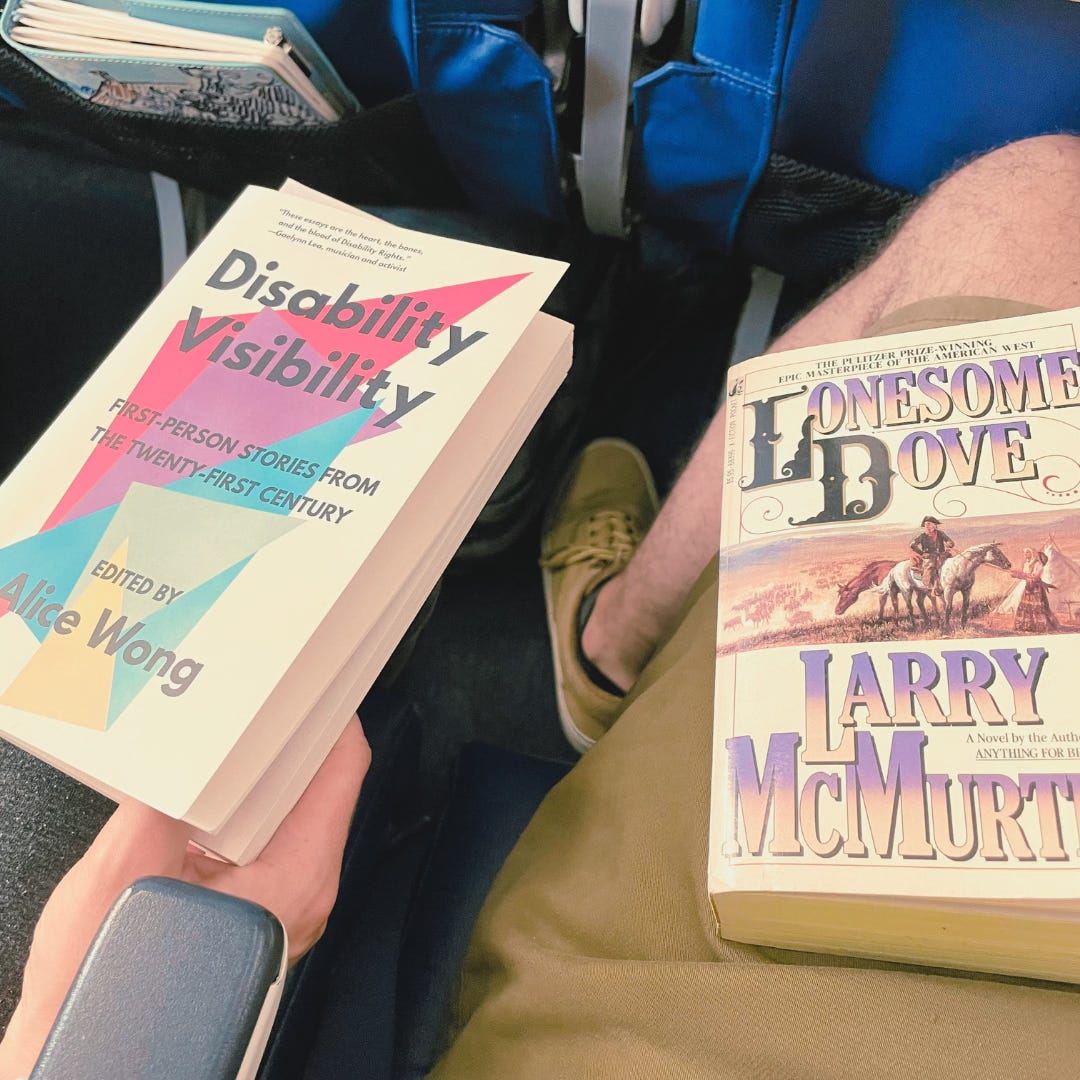

Here’s what this looked like for me: I kept a journal in my small, daily bag, and a spare one in my larger backpack. In addition to my preferred writing pens, I carried with me something to add texture and color to my pages: a few sheets of stickers, plus a small pack of dual-color highlighters. This way, I could make my pages look a little extra cute, but with minimal effort—not to mention the boosted sensory experience that transparent colors and glittery frog pancakes can add to your day.

What about you?

If you have any divergent travel tips (or needs!) you’re willing to share with all of us, I’d love to hear about them <3

I am never not in gratitude to Devon Price when I use the word, “constellation.”

I always take my own pillow (if going by car) and some art supplies and a headband with built in earphones so you can lie on your side comfortably, so if I can't sleep I can listen to something. It can also go over my eyes.

I love your description of unmasking being like restoring an oil painting.... Adding and taking away.

I'm inspired to get stickers now :) Just love the way you articulate your experience - it helps me reach deeper levels of understanding of my own unmasking process and the layers of choice that are available (and that it's OK not to always see them). Best description of the need for alone time ever - a vitamin you need higher doses of. Yes! Thank you.